With the exceptions of two overnight transits in cities, my four-week visit around Tanzania was spent solely in game parks and game reserves, where I had only positive experiences. All the locals I had a chance to speak with, Tanzanians and foreign worker residents (mainly from charitable non-governmental organizations), were warm and welcoming. I recall only two mildly disconcerting incidents, both involving low-level officials. At the entrance to one of the southern parks the ranger in charge of admitting tourists had a diffident attitude bordering on hostility. After a 15 minute exchange with my guide (in Swahili) during which she periodically cast suspicious looks in my direction, papers were vigorously stamped and we were allowed to proceed. I never found out the cause of the hold up, although my guide repeatedly assured me this was nothing unusual and that I should not concern myself about it. The second episode was a more direct although ultimately benign confrontation with a uniformed policeman. My guide, ranger and I were returning to the Serengeti National Park Western Corridor gate after an excursion that had taken us outside the park to visit a local community school and from there to the nearby shore of Lake Victoria (Africa’s largest lake). As we were slowly driving in our open game-viewing vehicle through a village with a busy market in full swing on both sides of the road, we were stopped by a uniformed policeman. My camera, which I had not used in the past few minutes, was hanging around my neck. The policeman addressed himself directly to me in fluent English and proceeded to sternly lecture me about taking his picture and that of the people in the market (I hadn’t), and that I had “no right and could get arrested for this.” Not wanting to make an issue of this and concerned about my companions who were visibly startled by this outburst, I merely listened to his tirade, after which he motioned us on. This incident was a reminder to me that there were in fact two Tanzanias, the tourist-oriented wilderness that cover over 25 percent of the country, and the far less idyllic remaining 75 percent.

All the parks and game reserves I visited were superb, each in its own way, and the abundance of game exceptional. However, while enjoying a day on the Rujifi River in Selous, Southern Tanzania, one of the largest faunal reserves in the world, which covers over 5 percent of the country, I was reminded of the constant and growing danger to the wilderness throughout the country. I was watching elephants drinking in the river when my guide remarked that while we were within the northeastern corner of the reserve dedicated to photographic safaris, the remainder of Selous is a hunting reserve. Tanzania has long been considered the ultimate hunting destination in Africa, and is to this day a big draw for safari hunters. Small wonder, considering that more than sixty species can legally be hunted here, including four of the famous Big Five: elephant, lion, buffalo and leopard. Now severely endanger, the rhino escapes the list, but not the poachers. Poaching incidents are frequently reported in the international press for illegal elephant ivory, rhino horn and bush meat traffic. Then there is the threat of the planned Serengeti Highway. In spite of growing international pressure on the Tanzanian government, construction is still scheduled at the time of this writing to start in early 2012. If the project continues as planned, a two-lane highway will slice directly through the annual migration route of over one and a half million wildebeests and zebras, effectively destroying the life cycle of these species.

In spite of the conservation and social issues in the country, I thoroughly enjoyed my visit to its premier wilderness areas. An additional pleasure were the internal flights that afforded me a great opportunity to view the country from above. While on approach to Arusha, I even had an eye-level glance at the summit of Mount Kilimanjaro with a narrow cap of snow.

Currency The national currency was the Tanzanian shilling (TZS) with an exchange rate of TSZ 1,425 per U.S. dollar at the time of my visit. The properties and other businesses catering to tourists I visited accepted U.S. dollars. Even the entrance visa (obtained on arrival at the airport) and park fees were assessed and paid in dollars.

Electrical Current Tanzania ran on 220 volts. A NW-135C adapter was necessary when using electrical outlets (the kind used in the U.K.).

Health And Vaccinations Since all of the places I visited (other than the Ngorongoro Crater) were malaria zones, I took the usual daily malaria medication. Precautionary vaccinations recommended by my local travel medicine clinic were hepatitis A and B, tetanus, typhoid and yellow fever. Interestingly, although only recommended by the United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention (C.D.C.), yellow fever vaccination was required for entry in Tanzania. I was asked at the visa desk whether I had yellow fever immunization. I answered in the affirmative but was not required to show my international vaccination records.

Tap water was said to be unreliable throughout Tanzania. Since all properties I visited, in urban centers as well as the bush, provided bottled water for drinking and oral hygiene, I took my cue from them and used solely bottled water for these purposes during the entire trip.

How To Get There There were no direct flights from the United States to Tanzania when I visited. I flew via Europe where there were non-stop flights from several cities including London, Amsterdam and Frankfurt. I took a flight from Amsterdam, which arrived late in the evening and required an overnight stay in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s business capital, before making my connection to Mikumi the following morning. For travelers to Northern Tanzania, Kilimanjaro International Airport, located 45 kilometers (28 miles) by well-maintained paved road from Arusha, the gateway city to the northern safari areas, was a more practical option.

Location In Eastern Africa. Tanzania borders the Indian Ocean to the east, Zambia, Malawi and Mozambique to the south, Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of Congo to the west, and Kenya to the north.

Measures Metric system

Money Issues An entrance visa had to be paid in cash. Starting March 1, 2011, a program was being rolled out by the National Park Department to accept only Visa and Mastercard payments for park fees. At the time of this writing, this was in effect only in Mikumi, Ruaha and Udzungwa National Parks, with more to come at an undisclosed latter date. In these parks, cash payments are no longer accepted. Visitors who do not use credit cards were able to purchase special smart cards in urban areas from designated branches of CRDB Bank of Tanzania.

Most sources I consulted advised against carrying much cash because of the incidence of crime and petty theft, especially in urban areas. However, ATMs were rare to inexistent outside of metropolitan areas. Since I was planning to visit safari destinations almost exclusively, I carried credit cards (which I knew would be accepted at all the properties I visited) and small denominations of hard currencies, which were readily accepted for small purchases anywhere I went. All the properties I visited had large state-of-the-art electronic safes in the guest rooms. I made sure I used mine and didn’t encounter any problems.

Technology In Dar es Salaam and Arusha I found electricity, running water, television, Internet, and cell phone access. In both cities, my hotel offered modern conveniences customary in luxury properties worldwide, including WiFi access from my room, although speed was moderate to slow and complimentary only in Dar es Salam. The Arusha property charged a steep hourly access fee. On the return flight, I had a layover of several hours at Dar es Salaam International Airport. There was a cramped Internet café there with a reliable and moderately priced WiFi connection. In the safari camps of the Southern Circuit, Internet access was limited, mostly due to the fact that electricity, and therefore router operation, was available only in the late afternoon and evening. Service was slow and occasionally erratic. Once in the Northern circuit, the properties I visited had electricity and WiFi access throughout the day and evening. The connection was reliable with moderate speed. Outside urban areas cell phone service was available but unpredictable.

Time GMT/UTC plus 3 hours

With less than 5,000 kilometers (3,000 miles) of paved roads in the country, the best travel option between parks was flying. Flights could be arranged directly by the properties with several bush airlines serving the various safari areas. All those I experienced ran 13-seater, or occasionally smaller, planes that were clean, in good repair and ran on a reliable schedule. The ground and flight staff were pleasant and efficient. Most flights made stops to pick up or drop off passengers in various parks along the way.

The distance from the airstrip varied from camp to camp, from 15 minutes to over one hour. However, transfers usually took longer as they were a great opportunity for a first and often most rewarding game drive. One drawback was that these various local airlines each served a specific area of the country and did not have synchronized schedules. When I left the Southern Circuit, my flight from Selous to Arusha arrived mid-morning, too late to catch the 90-minute flight to the northern part of the Serengeti. I had to overnight in Arusha before entering the Northern Circuit.

Shopping And Souvenirs Shopping was unremarkable and limited to the souvenir options available at the airport, hotels and camps. There was nothing of note in the southern camps. The choice was much better in the Northern Circuit were all the properties carried at least a small inventory of quality property branded safari wear, local crafts and trinkets. Additionally, a couple of the lodges had attractive gift boutiques that also offered a good choice of quality local woodcarvings, textiles and jewelry.

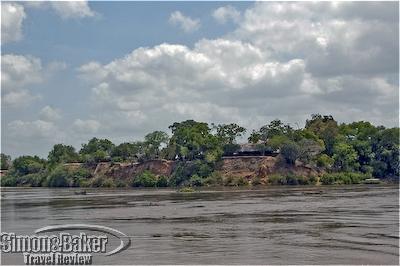

I then moved on to the Northern Circuit starting in the northern most part of the Serengeti Plain, along the Grumeti River, also known as the Western Corridor. From there I went on to one of the most celebrated safari environments in East Africa, the three million year old Ngorongoro Crater. I completed my visit with the intimate Lake Manyara National Park, a narrow strip of land between the Rift Valley escarpment and the large soda lake filled with flamingoes.